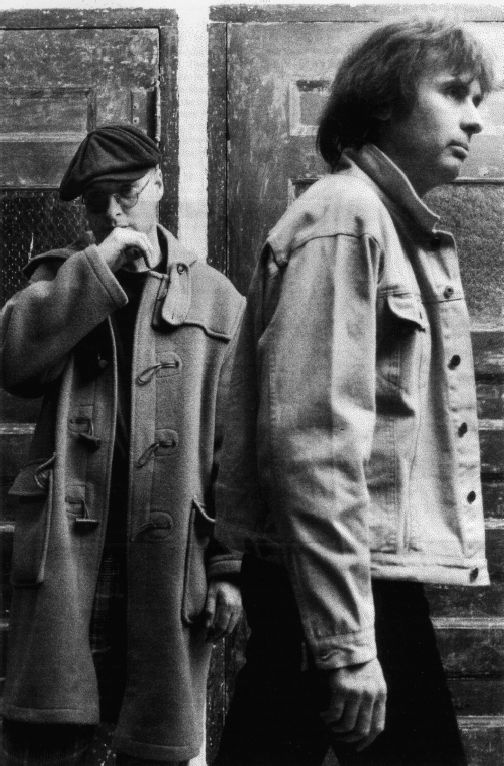

XTC: A-OKStyle Live: Music & Nightlife  Colin Moulding, left, and Andy Partridge -- the surviving members of XTC -- have a brand-new label and their first album since 1992. |

'80s Band' Orchestrates Comeback By Mark Jenkins The name XTC is usually prefixed with the phrase "'80s band," and that was the decade in which the English pop-rockers released such college radio favorites as "Senses Working Overtime," "Dear God" and "Love on a Farmboy's Wages." Indeed, casual fans may be forgiven for assuming that the group split after making 1992's "Nonsuch." But that's not what happened. Instead, Andy Partridge explains, XTC spent five years "in the fridge." That's the 45-year-old singer-songwriter's term for the period of enforced idleness after he and Colin Moulding, the band's only other remaining member, informed Virgin Records that they would not be recording for it again. "We were never going to make any money on that label," he says. "We were on the label for 20 years, and we were still in the red. We were living off of bits of publishing money, and I was doing some producing. It was crazy, because Virgin was making fine sums, but our deal was so stacked against us that we were never going to make anything. "In '92, I said, 'Look, can we have a sensible deal? Because we'd like to make a living after all this time. Or can we go to another label?' And they said no on both accounts. So that was it. It was 'down, plectrum.' We had to go on strike. They just sat on us for five years." Moulding and guitarist Dave Gregory did some session work to support themselves, but that wasn't enough. "It got so bad for Colin and Dave at one point," Partridge recalls, "that they were collecting abandoned rental cars. People just leave them, and they have to send someone out to get them and drive them back. "It's not really the sort of vocation," he says self-mockingly, "a rock god likes to find himself in." Finally Virgin let XTC go, and Partridge and Moulding founded their own Idea label, distributed by two small independents: TVT in the States and Cooking Vinyl in Britain. This week, Idea will release the first album of new XTC material in seven years, "Apple Venus Vol. 1." Written in 1992-94, its 11 songs were recorded in a style the band calls "orchoustic": mostly acoustic guitars and keyboards, accompanied by neo-baroque orchestral arrangements.

XTC also worked on an album of electric-guitar rock songs, and Gregory (who plays on "Apple Venus") quit the band in frustration when Partridge decided he didn't want that to be their first out-of-the-fridge disc. "I thought it would have been kind of dangerous to come out first with the upbeat, kind of wham-bam thing," he says. "I would rather people had the sense that my songwriting - largely mine, but Colin's, too - had moved through a different area. And I just like the idea that people see it in the right order." For those who'd prefer to hear XTC play electric rock, Partridge hopes that "Apple Venus Vol. 2" will be ready by the end of the year. "After two years of writing material that had an orchestral, acoustic background to it," he says, "it was almost like being a vegetarian and saying, 'I need a sausage. I need a T-bone quickly.' So the later stuff was written with noisy, clamorous electric guitars. To clean the palate." One reason that XTC can return to the studio soon is that the band abandoned live performances in 1982, after Partridge began experiencing panic attacks onstage. The band's refusal to tour has further typed the group as difficult, and Partridge as a troubled recluse. On a recent promotional tour in the United States, however, the singer was charming, playful and outgoing. It's Moulding, he claims, who is "pathologically shy. We're both stay-at-home kind of people, but he possibly even more than me." XTC made its first EP in 1977, the year of punk, so the band was initially classified with groups like the Sex Pistols and the Clash. It's been a long time, however, since XTC had much use for noisy electric guitars. With the release of albums like "English Settlement" and "Skylarking," it became clear that Partridge and Moulding (who usually contributes two to three songs per album) were most strongly influenced by the eclectic, circa-1967 sound of the Beatles, the Beach Boys and above all the Kinks. Like those of the Kinks' Ray Davies, XTC's songs celebrate farm boys, church bells, village greens and other landmarks of England's vanishing village life. To judge from "Apple Venus" songs like "Greenman" and "Harvest Festival," someone in XTC must spend a lot of time tramping country paths and dozing by haystacks. Or at least dreaming about such activities. "That'll be me, the indoor bookworm," says Partridge, chuckling. "I sit in the dark with my books and translucent skin, and I write songs that happen out in the fields, at sea, on the hills and in the woods. And then Colin - who goes for long walks and used to be a groundsman and does his gardening - his songs seem to take place in the parlor, the front room, the kitchen, the shed. So I guess we're secretly hankering after the missing part of our psyche in some way." Partridge and Moulding remain in Swindon, a town about a hour west of London, where they've lived most of their lives. (A Navy brat, Partridge spent the first three years of his life in Malta.) The songwriter speculates that this small-town lifestyle explains why XTC has an American cult following that dwarfs its British audience. "Why do Americans like us? Maybe for the same reasons they like the double-deckers. Perhaps we're exotically English." Living in Swindon, however, has apparently done the band no good with potential British fans. "We come from a comic town," Partridge explains, comparing XTC's home to Akron, Ohio. "Everybody's got a joke town, and England's joke town is Swindon. England's a big village: People from that street don't talk to the people from that street. It's all very small, and rather small-minded." This may be why, he suggests, the British reviews for this album are "five-star-type reviews, but they're kind of begrudging." He puts on an exasperated voice: "'Oh, these yokels, these egghead pop boffins are brilliant, I suppose.'" |

|

|

Despite Britain's muted enthusiasm for Partridge's work, the songwriter has been described as "the quintessential Englishman" - reserved, eccentric and suspicious of modernity. (He detests automobiles, which he describes as "petrol-driven murder machines.") "I do have a bit of difficulty expressing myself emotionally," he muses. "But as not as bad as a lot of Englishmen. I'm reasonably Latin for an Englishman." In fact, the songwriter expresses his emotions clearly on several "Apple Venus" songs, including the new-love ode "I'd Like That" and the bitter "Your Dictionary," an artifact of his mid-'90s divorce. The latter dealt him a serious financial blow while the band was on strike. "There's always been somebody to come along and take money away," he says with a remarkably sanguine chortle. "Still, it ain't about the money. Thank goodness." What it's about, of course, is the music of "Apple Venus," which Partridge painstakingly constructed over several years. The album features more orchestrations than any previous XTC album, and the songwriter did nearly all the arrangements. "Because we were stuck in limbo and couldn't work," he recalls, "I sat down with my one finger at a sequencer, and did choices of instruments, choices of lines, until I got it right. I don't write music. I have no concept of how one arranges, really. It's all a bit primitive and intuitive. Until a thing's right, I don't stop. Someone who's more adept at arranging could probably do it in a fraction of the time." Partridge admits that "my keyboard technique is nonexistent. You're talking to the fellow who's been known to make a cardboard hand when he found a good chord. I'd run into the house and put my hand on a piece of cardboard and draw around it with a marker. And write the name of the song on the hand. Until I bought a sequencer, I'd make these hands, or write on the keys." Because he ran out of time, Partridge turned to professional arranger Mike Batt for help with "I Can't Own Her" and "Greenman." For the latter, Batt "injected a little more Vaughan Williams into it, which was what I required." It wasn't until after finishing the album, Partridge says, that he began to understand his craving for orchestral arrangements. "Someone asked me if I worked with an orchestra because I like the classics. And I really had to think about it. I do like the classics, but they don't really speak to me. But as a kid I listened to the radio a lot. There was no such thing as pop radio in England at the time. All you had on the radio then was selections from 'My Fair Lady' or 'South Pacific' or whatever the show, and 'light entertainment' - some orchestra leader playing some ditty from the day with his orchestra. "I wasn't aware as a kid of this stuff making an impression on me," he continues, "but I now sincerely think it did. I think I rather underestimated the pungency of 'light entertainment.' That's why I wanted to hear an orchestra - not so much Mozart as Mantovani." Most rock auteurs eventually become producers as well as songwriters and arrangers, but XTC has always worked with outside producers. (For "Apple Venus," they were Haydn Bendall and Mick Davis.) To Partridge, though, a producer is "a funnel through which I can talk to other members of the band. If Colin reads this he'll get really huffy, but it's been so that I can ask them, tell them, and suggest things to them. They'll accept it coming from another person, but they won't accept it from a contemporary - coming from a person the same age as them who lived on the same council estate. "I can say the simplest thing, like 'I think you're out of tune. It sounds a little sour.' If I said that, I'd get, 'Why don't you just [expletive] off?' But if say to the producer, 'I really think he's out of tune,' the producer can then say that through the talkback, and the reaction will be, 'Oh, okay.' "It's because we were raised in each other's pockets," Partridge says. "We both went to the same schools. I found that I needed assistance in producing Colin and Dave. And maybe they thought they were being produced by a producer." Partridge pauses for a moment to consider the implications of this disclosure. "That's evil, isn't it? I'm a nice person, really. That's just how I get the art achieved." |