Light! Camera! XTCion!

Trouser Press

January 1981

By Scott Isler

Swindon, England; April 1980. XTC, those four local lads made good, have received a gold record for Drums and Wires, their third LP, and there's dancing in the streets.

Freeze frame; reverse. Could we have a close-up of that gold record, please? Well, actually, it's a gold record from Canada; the album sold 50,000 copies. Now pull back to a long shot of the town. Looks pretty quiet. Poetic license! The action is over here; see that park? That small group of people cavorting on the grass—that's the band, a photographer, a record company press officer...[Yawn] Roll 'em.

To memorialize this joyous occasion, XTC is posing with its newly-acquired trophies for an al fresco photo session. For one they lie in a row on their backs, eyes closed, hands folded on stomachs; the framed gold records are propped up for tombstones.

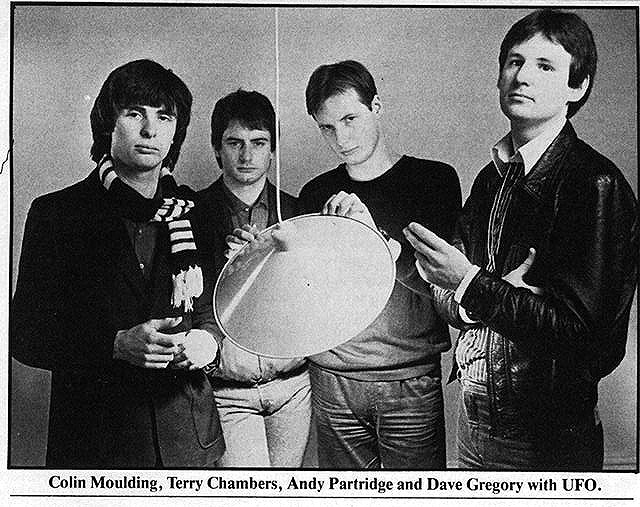

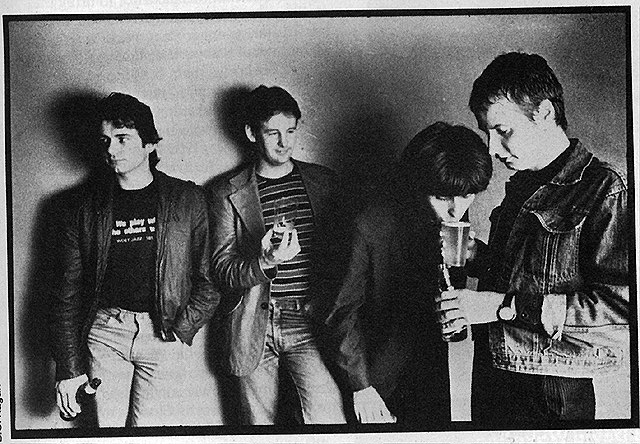

Humor (in all its shades, not just black) is an XTC trademark. Singer/guitarist Andy Partridge chose the band's name for easy visibility when scouring the music press for references to them. His witty lyrics reflect a bubbly if not downright giggly personality, but the rest of the band—singer/bassist Colin Moulding, guitarist Dave Gregory and drummer Terry Chambers—are also genuinely friendly, down-to-earth types. Given XTC's spotty chart success in the past, their lack of pretension is a useful survival technique; a more self-conscious band would have committed mass suicide by now.

“Gettin' a gold album from Canada isn't quite the same as gettin' one from England,” Moulding, 25, admits in his West Country twang. He says he will give his to his wife: “She can do what she wants with it—make it into a tea tray.” Partridge, 27, says he's giving his to his mother—“our old dear,” as he invariably calls her:

“I should feel too big-headed havin' it on the wall. People come in and say, ‘Hey, what's that?’ and you've got to spend 10 minutes explainin' it to them. Our old dear will love it. She'll have it up in the hall and polish it religiously.”

One way XTC retains its perspective is by staying based in Swindon, a grey, low-profile railroad center (population 100,000) 70 miles west of London. “This place must be duller than Akron,” Chambers observes dryly, but the band seems to enjoy its cultural isolation compared to the capital's neurotic trendiness.

“Living down the road has its advantages,” Moulding says. “Being involved with that cliquey sort of thing would get me down.” Chambers adds that “we're not great party-goers” and notes that in London XTC is considered “four pretty faceless characters. I quite like that idea.” While hardly anti-social, the band members respect each others' privacy; Moulding says they don't see each other much in their spare time. Partridge, recuperating from an intensive US tour promoting Drums and Wires (“I came back an absolute vegetable”), notes, “You see enough people on tour in two to three months to last you two to three years.”

New York, New York; October 1980. Partridge, Moulding and Chambers are circulating about Virgin Records' Greenwich Village offices, strategically dividing and regrouping to handle as many interviews as possible. Gregory, the newest and shyest member, is in midtown hunting (more) guitars. Yes, XTC is in town to kick off another soul-destroying tour. But wait! Is the band condemned to suffer these periodic torments indefinitely?

Not really. Unlike the Drums and Wires tour, which had them playing almost six nights a week for two months, XTC's schedule is less brutal this time—largely because most of the time they're supporting the Police, an act big enough to demand a day off for every two shows in a row. Some groups might resent a second-fiddle position, especially if they'd been together four years, released four albums and seemed perpetually on the verge of making it big. XTC, though, isn't one of them.

“Support bands have never got anything to lose,” Partridge posits cagily from behind a desk. “If you're better than the other band, great; if you're not better, you're just support anyway. We stand to convert people who wouldn't necessarily come to see us.”

Such pragmatism is an XTC watchword these days. It led the band to contribute a song to Robert Stigwood's punxploitation film, Times Square—which Partridge was at first leery about—for the same reason they're touring with the Police: exposure. (Significantly, Virgin has just switched to the Robert Stigwood Organization for US distribution. Stigwood himself attended XTC's first tour date, headlining at New York's Ritz, and reportedly was impressed. Maybe if he loses the Bee Gees...?)

The final element in the XTC popularity equation is, of course, a new album. Black Sea will be released in the US while the band is on tour. In this case, the usual pre-release high hopes are bolstered by the record's reception in England a month earlier. Artists tend to prefer their latest work automatically over past accomplishments, but XTC can be excused for considering Black Sea their most consistent work to date. “How do you feel?” Moulding asks, turning the tables on his interviewer. “Do you think it's the best thing we've ever done? I think it is.”

XTC's problem might be an overdose of individuality. Ever since their 3D EP came out in late 1977, the band's wacky, gregarious music has hovered around the fringes of new wave consciousness without receiving a full welcome. The band goes back as far as 1973, when Swindon's “Fab Three”—Moulding's term for himself, Partridge and Chambers—first got together. With numerous fourth members, they annoyed the local populace under various aliases: the Helium Kids, Star Park, Snakes, etc. The band got some demo tapes together and became XTC in 1976, with organist Barry Andrew [sic] holding down the revolving fourth spot; he has since gone on to Robert Fripp's League of Gentlemen. (“Keyboard players tend to leave of their own accord,” Moulding muses. “Guitar players tend to be sacked.”)

Although XTC's delightful quirkiness soon won them a cult following, two LPs (White Music and Go 2) and a stream of 45s failed to reach a mass audience. Drums and Wires, released toward the end of 1979, seemed to break the curse, containing the British Top 20 single, “Making Plans for Nigel.” It was also XTC's best-selling album, and not coincidentally the band's most restrained offering to date. “Nigel” and an American 45, “Ten Feet Tall,” even received some US airplay while radio was flirting with “new wave.”

Flushed with relative success, XTC next released the prophetically titled “Wait Till Your Boat Goes Down” 45 in England. It did. Fast. Fortunately for the band, they were too busy slogging their brains out on that first full tour of the US to notice that “Boat” rose (sic) to number 75 before sinking without trace. After recuperating in Swindon, XTC put together Black Sea this summer. The first 45 from the album, “Generals and Majors,” put them back in the record charts' good graces. Its follow-up, “Towers of London,” built on the momentum. For the moment, the US remains immune to XTC—but they have a friend in Robert Stigwood.

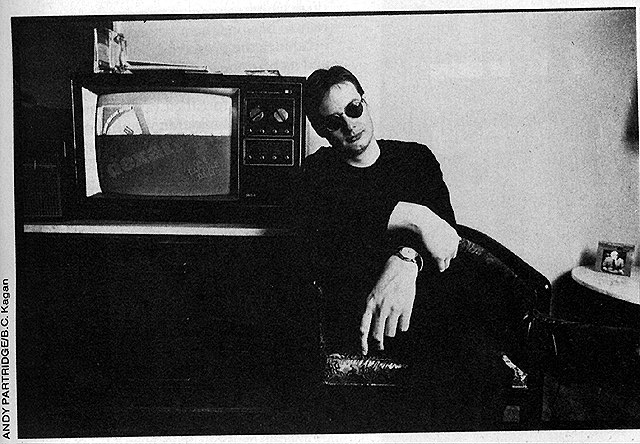

The band's ringleader admits he's not much to look at. Andy Partridge's close-cropped blonde hair frames a high forehead, eyes hidden behind spectacles (offstage), a prominent nose and thick lips. The lips are almost always curled in a smile, though, and out of that forehead have come some of the most ridiculously clever—sometimes just plain ridiculous—songs anyone has recorded in the last three years (“I'm Bugged,” “Life Is Good in the Greenhouse,” “Reel by Reel”—you get the idea). As usual, he is dressed in black: black slacks, black shirt (over a white “Santa Dog” T-shirt, however) and black sneakers. Also as usual, he maintains a cheerful attitude even while nursing a cold, dreading that evening's one a.m. show and recalling XTC's last American tour.

“'Burnt-out' is the word. We'd been a flaming comet and were just a pile of rubbly ashes by the time we got back. I think I cracked up in a minor sort of way.” Even worse than the exhaustion, he adds, was knowing that once they returned to England a new album would be expected of them. Hence their vernal seclusion in Swindon. “We have these periods of hiding away, but if you don't have them you just don't want to do anything at all.”

Black Sea was produced by the ubiquitous Steve Lillywhite, who first worked with XTC on Drums and Wires. “We wanted to do it ourselves,” Partridge says, “but the record company—” “They don't trust us,” Chambers breaks in. “They still think we're a bunch of jokers.” The drummer wears a white T-shirt, blue jeans and brown boots. If not as fanciful in his language as Partridge, he's no less forceful in his opinions.

“I think we just have a producer as a referee, really,” Partridge continues. Yet if Black Sea had been self-produced “I think it probably would have been more satanic,” he leers. “My state of mind at the time was not amazing; it was very black. People were buying copies of Sandy Lesberg's Violence in our Time and leaving them around for casual browsing. It's just the worst photographs you could ever imagine in one book: Belsen, child molestations, murders. There were loads of copies strewn around the studio like church pamphlets at a bloody Salvation Army meeting. You'd sit down with nothing to do, pick it up and flip through it”—he emits a gasp of horror—“'Fuck!'—chuck it away and be really depressed for the rest of the day.”

Employing perverse XTC logic, the band decided that its new album cover should look as different as possible from Drums and Wires' bright, Matisse-like collage. The result is a stagy photograph of the band in diving gear with assorted nautical props and backdrop. “We went for a photograph that was detailed, dark and somber—a period feeling rather than up-to-date art,” Partridge explains. “Then we felt pressured to find a nautical title that also fit the claustrophobic atmosphere we were feeling at the time.”

The above doesn't sound very promising, but Partridge adds that he's quite proud of his lyrics this time around, which he feels “are more coherent than ever before.” He cautions that “some of the songs are very schizophrenic; there are very up songs and very down songs.”

“Rocket from a Bottle”—“just a straightforward ‘I'm exhilarated’ song”—and “Sgt. Rock” (“the most irrelevant song on the album”) are clearly in the former category. The other extreme, however, provides Black Sea with its most intriguing moments. “No Language in Our Lungs,” according to its author, deals with the impotence of speech.

“When you're speaking you never get across what you really want to say. You can only give quick sketches of what you're thinking. I don't think anybody can communicate; they can only use certain sets of patterns. You can never get emotions into words. I do honestly think that speech is basically outmoded.” (“Hence most of the songs never come out as you intended,” Chambers wisecracks.)

“Respectable Street” protests society's double standards—one for its children, a looser one for wife-swapping elders—and “Living Through Another Cuba” is a genuinely fearful yelp over not-so-Cold Wars. “When you're in England there's nothing you can do; you're stuck between the superpowers. It's like being a ballboy at a tennis match.”

The album's most controversial (and, significantly, concluding) track is sure to be “Travels in Nihilon.” The title comes from Alan Sillitoe's surreal novel about an anarchic European country opened up to outsiders for the first time after World War II. The band creates an almost unbearable seven-minute block of sound; chaotic music and a threatening, chanted vocal fuse over a tribal drumming pattern. The purpose of this aural assault is rather personal.

“The meaning of the song for me is how people never learn about fashion trends, things like that. They always get duped. I was duped by the punk thing. I thought this was gonna save the world. That's the last time I was duped. I can see it happening in England now with 2-Tone. People leapt on it so quickly. It's sort of, ‘You'll never learn.’ People spend too much time sitting around with the trappings and not the real human core.”

Why the almost frightening sound? “So people would think about it more, I don't know.” Partridge shrugs it off but Chambers holds him to the subject: “The atmosphere you were trying to convey to us when we were putting it together in the studio was ‘living hell.’”

“It just got out of hand in the studio,” Partridge concedes. “We created a bit of a Frankenstein. Actually, there were two and a half minutes of drums cut out of the intro [for engineering reasons; Black Sea still runs close to 50 minutes].

“I like Terry Riley and Philip Glass—music that, once you hear what it's gonna do, you know will do that for the next 20 minutes, like a reliable roll of textured cloth. ‘Nihilon’ doesn't go anywhere; it's just a big texture. It had to be long to work; ideally it should take up one side and just be all drums except for a bit at the end.”

Nor is the song's wrap-up position at the end of the LP unintentional. As Partridge colorfully explains, “It's like you had an excellent four- or five-course meal and on the way out of the restaurant you pick up a toothpick and stab yourself in the tongue.”

Colin Moulding is the closest XTC comes to Group Heart-Throb. A shock of dark hair frames his face and accentuates dark, heavy-lidded eyes. Like Partridge, he dresses XTC Casual: tweed jacket, linty black cords, new white sneakers. Moulding is the band's “other” songwriter, not as prolific as Partridge, yet his tunes have consistently been XTC's most popular singles (“Life Begins at the Hop,” “Nigel,” “Generals and Majors”).

Moulding recently declared his independence by recording a solo 45, “Too Many Cooks in the Kitchen” (under the pseudonym “the Colonel”) at the end of the Black Sea sessions. “It's very different from what XTC does,” the soft-spoken bassist says. “I'm not saying XTC couldn't have done it but it would have stuck out on the album.” “Like a rock cake,” Partridge observes. “I personally find it too sickly.”

Partridge's own solo activity is marked by a fascination with studio technology. He contributed a 20-second “History of Rock 'n' Roll” to Morgan Fisher's Miniatures compilation, and early this year released Take Away/The Lure of Salvage, a dub LP made up of XTC recordings. He experimented with the dub technique of rearranging individual tracks two years earlier with Go +, an EP based on Go 2. Take Away might have been therapy to keep Partridge from thinking about the dismal failure of “Wait Till Your Boat Goes Down,” a gloomy dirge which he claims is the best song he ever wrote.

“Up until it not taking off when it was released, I thought, ‘This is gonna be our “Hey Jude”: this is gonna catapult us to number one forever.’ It was the biggest kick in the bollocks I ever had about something failing. I had a lot of faith in it.”

XTC's unpredictable fortunes are tied to a minor identity problem. Most English bands fall easily enough into certain categories—ska, punk, heavy metal—but Andy's gang may be too clever for their own good. Aside from a penchant for crunching rhythms and eccentric lyrical concepts, XTC refuse to be pigeonholed. Fans like to relate to a tangible image; Partridge, with his contempt for the vicissitudes of fashion, doesn't make it easy. How many other rock musicians paint miniature soldiers?

“It's a mixed breed we've been playin' to lately,” Chambers says. “Mainly the intellectual breed, I think,” Moulding adds, although Chambers has noticed more young girls turning up at gigs. Moulding notes that XTC's arrival on the music scene inspired a number of clone bands. “Now it seems we're not hip to be cloned.”

“We're a long way away from being fashionable in England right now,” Partridge agrees. “A lot of kids now consider us old men.”

“We have our ups and downs,” Moulding concedes, “but we have a basic need to keep this thing going.” “It's a very slow process,” Chambers says. “We've made four albums; none of them were a blazing success but each progressed in popularity.”

“We all feel privileged to be doing what we're doing,” Moulding says humbly. Then he smiles, brightening up. “That's something to live for, isn't it.”

Cut. Print.

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to Melanie Bouchard]