In April 1985, record shop displays everywhere took on a strangely dazzling hue as 25 O'Clock by THE DUKES OF STRATOSPHEAR appeared, blazing a trail of meticulously authentic '60s psychedelia against a climate of synthetik MOR and multi-million selling dross.

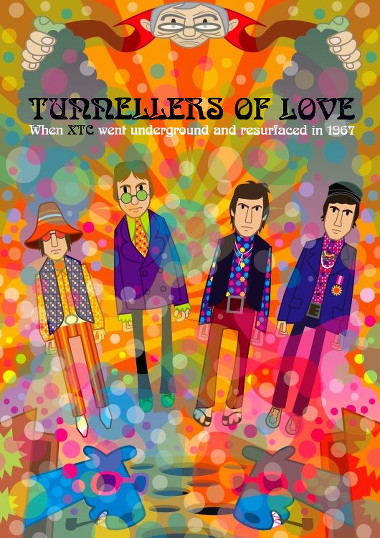

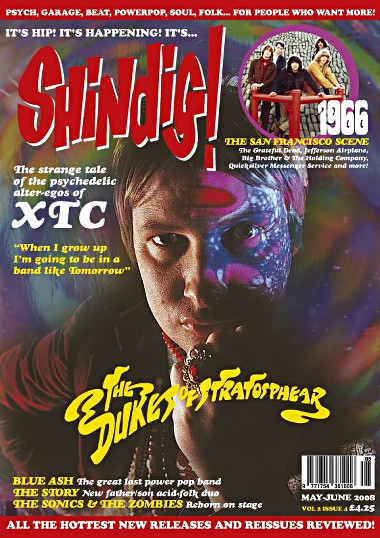

So what was the true identity of these out-of-time musical warlords? Why, 'twas none other than cult pop mavericks XTC! Who else? Follow us as Dukes lynchpins ANDY PARTRIDGE and DAVE GREGORY spill the beans on catholic knitting, Mott The Hoople's organ and Deryck Guyler. Don't worry, it'll all makes sense eventually. MARCO ROSSI nicks the comfy seat. Illustration by PETE FOWLER.

IT'S APRIL 1, 1985, AND I AM leafing with listless disdain through the new releases in Poole's Our Price record store in search of anything at all that 1night feasibly float my boat. More fool me.

The boat in question has been repeatedly holed below the waterline by salvos of soulless, characterless, identikit '80s pop fired across the nation's bows by the pirates of the airwaves, and is in imminent danger of going down with all hands. All hope of salvation is gone... then I chance upon the synapse-searing dayglo sleeve of a record entitled 25 O'Clock by a group called The Dukes Of Stratosphear (who the?!) and I know my life is saved even before I get it home and frazzle in the UV rays of its extraordinary contents.

23 years later, I am one of two Shindig! conscripts standing outside the Swindon home of Dukes/XTC lynchpin Andy Partridge, waiting with bum-puckering trepidation to speak to him and his fellow traveller, musical magus Dave Gregory, about The Dukes Of Stratosphear and exactly how XTC's career came to take this enriching detour.

Trepidation? It's more like being a little awestruck, really. The music created under the uncommonly florid XTC umbrella has meant more to me over the years than that of any other band this side of The Beatles — an apt comparison as they were arguably the first band since The Fabs to similarly interpret pop music as a playground with no fences in any direction. (Furthermore, in Partridge and bassist Colin Moulding they boasted two songwriters each capable of being both Lennon and McCartney.)

I bought, and was duly rocked on my heels by, absolutely everything they released from their '77 debut XTC 3DEP onwards. Their songs soundtracked the courtship of my wife and the birth and upbringing of my kids. One of my proudest musical accomplishments as a fledgling guitarist was figuring out how to play — with a tail wind, and a prayer to St Jude — Dave Gregory's gorgeous, wristy solo from '79's ‘Real By Reel’.

It is often said that you should never meet your heroes — but what do people know? Over the course of the afternoon, Partridge and Gregory (Sir John Johns and Lord Cornelius Plum, to give them their noms-de-Duke) prove to be impeccable hosts and exhilarating company. Unlike your average rock bozos, they are gifted with an almost photographic recall of events, unflinching candour, a rare erudition and an ever-present, percolating wit. Andy's picaresque, free-wheeling narratives are complemented and illuminated by Dave's wise, drily humorous recollections, and there is a palpable respect between them which genuinely gladdens the heart.

The story of how avant-pop avatars XTC came to reinvent themselves as psychedelic pseers The Dukes Of Stratosphear — a name they nearly adopted in the first instance — is involved and circuitous, but the clues as to their covert lava lamp leanings were there from day one for those who cared to look. On the 3DEP alone we hear the word "psychedelic" whispered before Barry Andrews' berserk, atonal keyboard solo in ‘Science Friction’; besides which Andy asserts, in ‘She's So Square’, that the titular anti-heroine ‘thinks this is 1967’. Debut album White Music from January '78 contains a radical and shocking deconstruction of the Dylan via Hendrix touchstone ‘All Along The Watchtower’ — and it has subsequently emerged that ‘Citadel’ from Their Satanic Majesties Request was originally in the frame for a similar duffing up.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was around this era that the Dukes concept was first mooted. Dave Gregory was still some months away from joining XTC to replace departing maverick Barry Andrews when the band returned to Swindon following the recording of second album GO 2.

Dave recalls: “Andy had just come back and he had some advance tapes of GO 2 that he wanted to share. I was thinking ‘this is great’ — it was a real step on from the first record, they seemed to be going in the right direction, couldn't wait for it to come out...”

Andy had a different agenda on his mind, however. “When Dave came to see me at 12 Manchester Road,” he remembers, “I said ‘what are you doing at the moment? Are you busy? Because... I've always wanted to be in a psychedelic band’. I just felt like it was time to bring this bloody thing back.”

As far as Dave was concerned, “It was the daftest idea anyone could have suggested in '78! It was very late, we'd all had a bit to drink (“Breaker lager,” Andy interjects grimly), so I thought, ‘he's rambling’. I must confess I didn't take it that seriously because I knew how busy they were. But I thought, well, it's an interesting idea, I'll have a look and see if I've still got my fuzz pedal — and if they still make batteries for it! That was when the idea was first broached, but of course we didn't get the opportunity to put it into practice until five or six years later.”

Andy Partridge had in fact harboured an insatiable itch to be in a psychedelic group since his late '60s schooldays. Dave Gregory, one-and-a-bit years his elder, was at that time already something of a veteran of the youth club stage in St Peter's Church in Penhill.

“I used to go and see Dave in his band Pink Warmth in '68,” grins Andy. “He'd be there in his sleeveless waistcoat. I was really impressed with that, actually.”

“I had a friend, Terry Jackson, who was an apprentice saddler at the time,” Dave explains, “and he used to make little things from scraps... and we were just skinny lads! It didn't take much to make us a waistcoat or a vest out of leather with tassles on. It looked pretty good on top of a T-shirt or a tie-dyed granddad vest.

“We'd roll up there with whatever equipment we could scrape together. We had drums and guitars, but amps were always broken or just unavailable, so you never knew quite what was going to happen. It was just a need to get on a stage and show off in front of your mates, and just make this amazing noise with this electrical equipment. It was the electricity that was important. We couldn't have done it acoustically.”

“Yeah,” agrees Andy, “you couldn't offend your parents with a nylon string one. ‘Oh, he's tuning up again, how nice’... But with an electric, you'd just stamp on that pedal and go SQUEEEE, GGGGRRRR... that was great, that was a real parent upsetter.”

Fast forward 17 years to '85, and these teenage devotees of bendy psychedelic music and the liberating properties of unruly electric guitars find themselves in their early 30s, members of the same well-established band now eight albums down the line. For Andy Partridge, the dream of a psychedelic parallel career had never really receded. A “tentative drunken knockabout” with XTC during the sessions for English Settlement in '81 resulted in two spontaneous and swiftly forgotten pieces, ‘Shaving Brush Boogie’ and “Orange Dust’, but a later composition was destined to provide the key that would unlock the dressing-up box.

Andy says: “While we were mixing The Big Express ('84) I remember sitting upstairs in Crescent Studios and coming up with ‘Your Gold Dress’. I thought, I've got to find the dumbest riff... what is the dumbest riff you could do, you know? (Sings ‘Your Gold Dress’ riff): DER-DER-DER-DER... So that was it, I thought ‘I've got it’. I was really burning to do this, because somebody called Nick Nicely was in danger of trumping us.”

“Well, he had already trumped us,” notes Dave. “Yeah, but he hadn't done an album,” replies Andy. “It was ‘Hilly Fields’, the single. So I was dying to do this, but wondering “when in the bloody hell are we going to get the time?’ We were just really busy and thinking ‘no one's going to fund it’.

“At that time I was supposed to be producing Mary Margaret O'Hara, and I said to (producer) John Leckie, would you engineer it for us, because I hadn't done much in the way of producing; I really needed an experienced voice.

“I went down to Rockfield Studios, which is where we had to do this thing, and Mary and her band flew in. I never saw her for a few days — she was off praying in local churches... and knitting. Her and her band would come out at night and just hang around, and then they woke me up at about one in the morning, after I'd been asleep for an hour, saying ‘we wanna start’! So it was like, well, John's arriving here tomorrow so let's go through some of the material... and they couldn't play in time, it was horrible. So I said ‘look, can you rehearse to a click track?’ Gasp! They froze with horror.

“The next day, their chubby little manager took me on a long walk down the driveway of Rockfield: ‘Er, Andy, come along, I wanna have a word with you. Mary Margaret doesn't think you're right — your vibe's not right, man.’

“Well, yeah, because I had asked them to rehearse. That had really offended them, so Mary immediately decided I was not right for the production. And I said ‘well look, John's arriving later on today, the studio's booked, band's here, just start with John’.

“And, er, ‘Oh no, man, she's heard that John's a member of the Orange People’... You know, the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh... ‘And she could not be in the same studio as somebody who promotes free love.’

“So that was completely fucked! I now found myself with a couple of weeks on my hands, and John Leckie now had a couple of weeks on his hands, so when John got there I said ‘look, you and me are fired, mate — too much of this free love nonsense, so we'll leave them to their catholic knitting and, er... John: Do you fancy making a psychedelic record?”

The time seemed right in every sense for the band to take that long-promised, spirit-replenishing magical mystery tour. Seasoned XTC watchers had long detected the intermittent appearance of a barely repressed psychedelic mindset — or at least, the lusty, vigorous pursuit of a natural high — in Andy Partridge's songs (witness the enraptured, experiential lyrics of ‘Senses Working Overtime’, or the sinuous Indian inflections and love-conquers-all sentiments of ‘Beating Of Hearts’).

Lately, however, a sense of frustration and disillusionment seemed to have been creeping in under the floorboards. ‘Funk Pop A Roll’, from '83's Mummer, was a focused, turbocharged broadside which skewered the hollow cynicism of the music industry and the unthinking, reflexive clutch of consumerism in a series of devastating couplets (“Everything you eat is waste, but swallowing is easy when it has no taste”... “The young to them are mistakes, who only want bread but they're force-fed cake”).

Meanwhile, ‘Train Running Low On Soul Coal’ from the wearying sessions for '84's The Big Express — originally released in an Ogden's-referencing round sleeve — appeared to address a crisis of confidence in vividly bleak terms. Partridge, a master without peer of the extended metaphor, used the declining industry of once-proud steam town Swindon to mirror an enervating sense of age-related artistic redundancy: “Think I'm going west and my sprinter's speed is reduced to a crawl, my rails went straight but straight into a wall... It's the wall on which they dash the older engines”.

The timely advent of the Dukes Of Stratosphear therefore represented, in comparative terms, a giddy release from responsibility and constraint. “You didn't have to be yourselves,” remembers Andy. “It was a fancy dress ball. It was ‘let's have some fun’. Let's not have to be us, let's put the clothes on, put the mask on, get back in touch with what you wanted to do as a schoolboy. ‘When I grow up I'm going to be in a band like Tomorrow’, or ‘I'm going to be in a band like Pink Floyd’, and of course you grow up and you find yourself in a band — which is a dream in any case — but it's nothing like Tomorrow or Pink Floyd.

“You didn't have to be yourselves, it was a fancy dress ball. It was ‘let's have some fun’. Let's not have to be us, let's put the clothes on, put the mask on, get back in touch with what you wanted to do as a schoolboy. ‘When I grow up I'm going to be in a band like Tomorrow’.”

“It was a case of let's have some fun and say thank you in music to the bands who made our schooldays so psychedelically interesting.”

Andy subsequently ran the idea past Virgin Records. “I rang them up and said ‘look, we'd like to be another band, we've got some time on our hands, I've got some ideas for songs, if we can book a cheap enough studio, can we do a record?’ Of course they liked the idea because it was ex-contract, it was a free album for them.”

John Leckie initially approached free festival figurehead Edgar Broughton, who was said to own a cache of vintage record ing equipment, but when much of this was found to be in need of repair Leckie secured the use of Chapel Lane Studio in the village of Hampton Bishop, near Hereford.

“It was a Christian studio,” Andy recalls. “John said there were some lovely old bits of gear in there — he got them to fax him a rundown. And it was so cheap, because it was where they made Christian albums! I think John told them we were a Christian band, which is why we were allowed in there. They didn't know who The Dukes Of Stratosphear were. They used to bake us a cake every weekend! They didn't bother preaching to us because they assumed we were already heavy duty Christians.”

The core XTC trio of Andy Partridge, Dave Gregory and Colin Moulding (rechristened The Red Curtain for Dukes purposes) were joined for the recording by Dave's younger brother Ian, known to and revered by Dukes fanatics as the redoubtable E.I.E.I Owen. “We didn't have a set drummer at the time,” recalls Andy — Herculean original drummer Terry Chambers had left during the sessions for Mummer — “so it was a case of roping in poor old Ian.”

“He was working,” elucidates Dave, “and I just said ‘is there any chance of you getting a couple of weeks off in succession? Andy wants to do this psychedelic record, how do you feel about it?’ He was very nervous about it, but I said come on, just have a laugh — it's just going to be a joke!’ So he came and stayed with us in this draughty little house next door to the studio, and just went in there and made the record.”

The record in question, 25 O'Clock, was to be a six-track neo-psychedelic gem recorded and mixed in a scant two weeks ‘for less than five grand’, yet graced nevertheless with a dizzy generosity of ideas and an absurdly gratifying overabundance of detail. To this day, it remains a bottomless lucky bag which repays constant rummaging.

The title track's Electric Prunes shudder and two questing, climbing key changes in the solo section betray a rare American influence — a thorny topic we will be returning to in due course. ‘Bike Ride To The Moon’ relocates the action to Blighty via the cosmos, a stirring evocation of Syd Barrett whimsy set to the sprightly gait of Tomorrow's ‘Three Jolly Little Dwarfs’.

‘My Love Explodes’ is a pell-mell, free-falling, literally explosive thrill ride referred to by Andy as “The Yardbirds' ‘Over Under Sideways Down’ mixed with The Pretty Things, or anyone who had an armful of maracas and a basin haircut”. The outraged, Woody Allenesque New York voice which emerges over the heavy fallout as the track disintegrates — “That is the most obscene... abomination of a song” — comes from a radio phone-in fortuitously captured by John Leckie following the airing of an a capella ditty from Tuli Kupferberg of The Fugs, deathlessly entitled ‘Hey, Go Fuck Yourself With Your Atom Bomb.’

The track which launched the Dukes' whole inner space mission in the first place, ‘Your Gold Dress’, emerges as the apotheosis of all knuckle-dragging, troglodytic riffs, contrasting with a beaming, fleet-footed middle section decorously adorned by Dave Gregory's vari-speeded, heavily compressed piano — a nod to the sterling service offered by Stones sessioneer Nicky Hopkins on ‘She's A Rainbow’.

Album closer ‘The Mole From The Ministry’, with its placid bed of wobbling Leslie piano chords and nodding slo-mo gait, was ‘I Am The Walrus’ and ‘We Are The Moles’ circling each other in a bath of jelly — a clear indication of the extent to which the Dukes knew and loved their source material. ‘Mole...’ even fades out and back in a la ‘Strawberry Fields’, during which Dave cunningly plays the riff from Go 2's ‘Life Is Good In The Greenhouse’ on Andy's trusty $7 Zippy Zither.

Astonishingly, the track was written “while Dave went to Birmingham to get some Mellotron tapes,” Andy says. “Fucking hell, we can't do this without Mellotron flutes! We were all suckers for Mellotron — we had originally bought it for Mummer, things like ‘Human Alchemy’.”

Dave says: “The tape we bought for The Dukes had flutes, cellos and augmented brass, which is just the typical sound that you instantly identify as a Mellotron.” “It sounds like fog when you play it,” muses Andy, “just this purple fog.”

Gear porn aficionados should also note that where possible, according to Dave, “most of the guitars and amps we used were '60s sourced. The most authentic fuzz pedal for that '60s sound was a regular Boss DS-1 from the mid-80s, they were perfect. I still use it!”

Rather surprisingly, “a synthesizer, a Roland JX-3P, did all those cheesy organ parts” — which would notably include the title track's keening Mike Ratledge-style solo. “We did have a Hammond organ,” smiles Andy, “but we were loaned it under the guise of ‘can we borrow your Hammond, Mr Verden Allen ex-of Mott The Hoople?’ And really, we wanted it so that we could get the Leslie cabinet, so we could put the voice and stuff through it. And he caught us doing it!

“John Leckie said ‘if you unscrew the back of the Hammond there's a socket in there, and you can put the mic through the amp and it will go out through the rotating Leslie speaker.’ And Verden Allen was sort of hovering because the Hammond was his baby, and he caught John, you know, with a screwdriver! ‘What you bloody doin'?’ ‘Oh, it's alright Verden, it will all go back as it was’. That was it, he went ballistic.”

“Me and Dave we're

the exact age and the exact demographic to

have been under the sheets with Radio

Luxembourg. We're from that school of psychedelia, specifically British psychedelia — and specifically British psychedelic singles — you

know, the refined, no spare flesh school of

psychedelia.”

ANDY PARTRIDGE and

DAVE GREGORY's Top Ten UK Psych 45s.

PINK FLOYD · SEE EMILY

PLAY (Parlophone, 1967)

A “how to” manual for

the art of the concise psych single. The opening melange of sounds says

“nothing will be the same from now on”. Made me desperately want to

be in a group when I grew up. If a paisley patterned shirt could make a

record.

TOMORROW · MY WHITE

BICYCLE (Parlophone, 1967)

A nursery rhyme, a slice of

pre-chewed bubblegum, a veritable mandate for looning. Beautifully realised

backward pieces threaded between the sound of a scurrying Sturmey Archer at

full downhill get-away-from-the-rozzers mode.

THE BEATLES · STRAWBERRY

FIELDS FOREVER (Parlophone, 1967)

Possibly king of all

pstrange psingles, this IS the sound of a dream. Blown away when I first heard

it and even though I now know how they did it, I'm still blown away. One of the

few times the Fabs actually used a mellotron and wouldn't you know, its finest

hour as well.

NIRVANA · RAINBOW

CHASER (Island, 1968)

An ersatz Bond theme for a non

existent film. Perfect day-glo blue soup of dramatic concerto piano, blaring

Cadillac horns, dolly bird chorus and it's all phased to flip! Was a tad put

out when those American fellows nabbed the name too.

THE MOLES · WE ARE THE

MOLES (Parlophone, 1968)

Our greatest portal to contemporary

psych was of course the radio and boy, were we reeled in at Sunday teatime with

the mystery behind this. Fluff Freeman said the beeb had been sent a key to a

locker at Paddington station and when they retrieved the mystery disc from

inside, well... “you all know who this group really are don't you?”

That's right, it was of course Simon Dupree & The Big Sound. Oh! Still good

though.

THE PRETTY THINGS ·

DEFECTING GREY (Columbia, 1967)

Ominous low rumble heralds

waltzing cutlery, wah-wah pedals and Phil May's Barrett-y vocal

“won-der-ing if you will say good-night — leave me a grave of

goodbye —" whirring sitar fades in, someone nails a drum-kit to a door

and all hell breaks loose. Producer Norman Smith must have shat his pants! Ends

with cheesy high-kicking valediction. All psychdelic high-life is here.

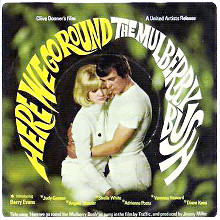

TRAFFIC · HERE WE GO ROUND

THE MULBERRY BUSH (Island, 1967)

It's November '67 and the

drugs have finally kicked in. Teenage Steve Winwood and his Black Country pals

go under, and in two-minutes-thirty-five take us on an amazing journey from

childhood to blushing adolescence to disillusioned adulthood, and back to the

nursery. Peerless musical genius at work, and check the absolutely enchanting

drumming.

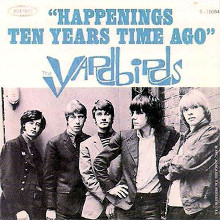

THE YARDBIRDS · HAPPENINGS

TEN YEARS AGO (Columbia, 1966)

Lightning captured in a

bottle here as Jeff Beck AND Jimmy Page play nicely together on this pryceless

slyce of purest psych nonsense. Possibly the first rap vocal, over Beck's solo,

where The Man recalls a conversation with a London cabbie. Great riff,

intriguing vocal, stunning guitar sounds, and with ‘Psycho Daisies’

stuck to the other side the disc is pure kryptonite.

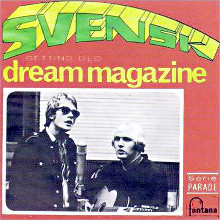

SVENSK · DREAM

MAGAZINE (Page One, 1967)

In which the lovelorn protagonist

yearns for a girl in a fashion spread, to the accompaniment of arco

double-bass, stirring chapel organ and out-of-tune 12-string guitar. Few people

could tune a 12-string in the '60s. “In wide-angle she is fine, in

telephoto she is mine”. The late Jason Paul, one half of Svensk,

relocated to Swindon and started a photographic studio and later a model

agency, among their alumni the lovely Melinda Messenger.

As told to Marco Rossi.

“Well, fair enough, we took his Hammond apart,” Dave points out.

“He wouldn't have known if he hadn't been lurking!” counters Andy.

The Hammond remained in situ long enough to provide a lambent backdrop to Colin Moulding's sole composition for the album, future-shocker ‘What In The World’ — like Zager & Evans, only brilliant — which is also blessed with a ping-ponging tumult of overlaid backwards guitars and found sounds redolent of ‘Only A Northern Song’.

“I basically brought a load of albums in and just spun them in by hand,” says Andy. “You know, bits of sitar, bits of trumpet off a jazz album. I found The Wit And Wisdom Of Benjamin Franklin in a junk shop — it was some American album with old actors trying to talk like Benjamin Franklin, so we thought we'd have a few things from it. I had no concept at the time that these were intellectual property rights, it was just ‘hey, that's a good noise’.”

‘Paul Revere's Wild Ride’ from the Benjamin Franklin album rode to the rescue in ‘Mole From The Ministry’ completely by chance, providing the whinnying horse which prefaces the song's middle eight. “We were lining up this quote, ‘after three days fish and visitors smell’,” remembers Dave. “John was running the tape and hoping that he was going to drop in at just the right place. But as the record was playing the previous track was still running, and the neighing horse was either part of the previous track and John missed it or else he put the stylus on the wrong track, but coming in just before that piano chord, it was like, oh that's genius... thank you, God!

“Things like that happened. It's amazing what happens when you have these time constraints, when you don't have time to think about stuff.”

By all accounts, John Leckie's contribution to both Dukes albums cannot be underestimated. “He is the Fifth Duke!” exclaims Dave. “He worked miracles. Without even having to be asked, he knew exactly what we were trying to do, the sounds we were looking for.”

Leckie's weighty psych credentials were forged in the motherlode, Abbey Road Studios: As a young tape op, one of his first jobs was with the Syd-era Pink Floyd. Furthermore, Andy points out that “if you look carefully when you watch Stones In The Park, about 100 yards back or so there's Leckie in a striped blazer...”

Patently, the right man for the job. “I don't even remember discussing anything with him,” adds Dave. “As soon as anyone had an idea, we would say ‘can we just put a bit of Mellotron in these four bars here?’ ‘Yeah, go on then’... Down it would go, and when the track was mixed you suddenly realise, here's the big picture — he would put all the pieces of the jigsaw in exactly the right place, in one pass. He didn't sweat anything at all.”

Leckie also knew just what was required to achieve enormous 360 degree phasing using three tape machines — a rare attribute in '85. “John had a way of making it pretty much controllable,” says Andy. “He had a voltage controller for the speed of one of the machines, and as you turn the voltage up or down the machine moves slightly slower or faster so you can actually sort of ‘ride’ the phasing. You can dial it in — ‘right, we want it to go nneeaawww’ — you can almost drive the thing.”

When 25 O'Clock was completed it was obviously going to require a suitably authentic brain-haemorrhaging sleeve design, and the Martin Sharp-inspired, deep-fried end result was put together by Andy at his kitchen table.

“I thought, what are the great British psychedelic sleeves, and I couldn't think of a better one than Cream's Disraeli Gears... and if you look at it, it's really tatty! They've just got photographs that they've scalpeled and cut out, they've drawn on them with fluorescent markers, then they just Sellotaped it down and it's like, how crap! But thought, well, if they can do it then I can do it on the kitchen table.

“So I just got some... not copyright-free art as such, but... I think one of them was The Complete Encyclopaedia Of Illustration by JG Heck, an old engraver, and I thought ‘well, everyone's nicking this stuff so I might as well nab it’. I'd take loads of books round to the photocopying shop and photocopy it all in black and white. I built it up very large — about twice the size, on a big bit of board — and then took it to a fellow called Dave Dragon... the impossibly-named Dave Dragon, but that is his real name... and said look, can you paint this so it's part of the way to Disraeli Gears? So he just sat down with fluorescent paints and painted the black and white photocopied artwork.

“Oh, another thing was, everybody had to supply a photograph so their heads could be drawn in a blobby psychedelic style for the back cover. Dave, that one that your brother supplied, he's all in denim? Is he looking out of a stable, or something?”

“It was taken when he was playing in a country band,” remembers Dave. “That's it! It's in sepia, he's all in denim, looking out of a stable — It was a case of redraw him, and don't put the denim and the stable in!”

Given that the prevailing winds were blowing, at hurricane force, directly in the Dukes' faces in '85, it is salutary to relate how Virgin Records reacted upon hearing the finished product.

“I remember going to see Simon Draper, who was head of A&R,” recalls Dave, “and he invited us into the office, and he was beside himself with joy — 'lovely, fabulous, fabulous’ — sitting at his desk, flicking his pen to it, like Keith Moon with his drumsticks! He said ‘listen guys, this is amazing, this is fantastic, we love it. Now, if you can do this in a psychedelic style, why can't you make us some hit records in an '80s style?’ But apparently it was a big hit in the office, so he said we'll release this on April Fool's Day, give it a special catalogue number and everything... But I think they just thought ‘we'll put this out, we'll put ‘Mole From The Ministry’ out as a single and see what happens’. Nobody else seemed to get the joke at the time.”

Andy thinks of it as “not ahead of its time exactly, but just a bit out of time, because as the '80s went on the revival of psychedelia gathered pace and got quite mainstream.”

The anonymity of the Dukes appears to have been compromised from the start. “Virgin sent a press release around saying things like ‘you'll be in ecstasy when you know who this is’, that sort of thing,” says Andy. “I begged them to keep it under cover, but they just said ‘Well, we're not going to sell as many unless we let it all out’.”

Mention of sales figures prompts one to question whether, as has often been claimed, 25 O'Clock outsold the contemporary XTC product. “It did at the time,” Andy remembers. “It sold approximately three times as much as The Big Express.” So why did it not appear in the charts?

“It didn't qualify because it was neither fish nor fowl,” Andy suggests. “It had too many tracks for a single and not enough for an album.

Dave adds: “I don't think we'll ever know exactly how many it sold, because at the time we were in litigation with our management and the record company in terms of what our actual sales figures were.”

“What with stuff being bought online and downloaded, it's a complete mystery as to how many discs we've sold,” reflects Andy. “It's millions, but I don't know how many. Not millions of The Dukes, but millions of the entire thing. But the figure was round about 90,000 Dukes as opposed to about 30,000 of The Big Express, and that was within a year or two of it coming out so I don't know what it would be now.”

A fortunate few at the time of 25 O'Clock's release were treated to a viewing of the highly evocative promo film for ‘Mole From The Ministry’ when it was broadcast on the Beeb's Old Grey Whistle Test. “It's the only video of ours that I am proud of, in the entire career,” says Andy. “It looks just right, it's ‘Blue Jay Way’ gone mental.”

“We were lucky to find that location as well, Nailsea Court, the country house and the lawn,” adds Dave. “Interestingly, Steve Somerset, who worked for Medialab with Godley and Creme at the time, wanted to make a film of 25 O'Clock. It was on to go ahead, I'm not sure why it never got made.”

“They probably approached Virgin and said it'll need funding!” laughs Andy. “It was to have been a treasure hunt feature film. I think he saw that book, that one where you had to search for a golden hare... Kit Williams, Masquerade... and he liked the idea of making a film with clues. The idea was that you could buy it on video or whatever and keep rewinding it to look at stuff in the background or hear what somebody says, which would lea you to a golden 25-hour clock which was to have been hidden in England somewhere.”

Following 25 O'Clock, the next XTC project was destined to be the Skylarking album from '86, recorded in Woodstock, NY with Todd Rundgren at the production helm — which is a story in itself. With the benefit of hindsight, it seems clear that the spirit of the Dukes fed into the project to a not insignificant degree. Andy's ‘Summer's Cauldron’ and Colin's ‘Grass’ are characterised by a beatific, pastoral calm, all airy suspended chords and wide-eyed wonder, while ‘1,000 Umbrellas’ refracts its lovelorn melancholia through a landscape of Magritte surrealism, backlit by Dave's ravishingly adventurous string arrangement. Colin's ‘Big Day’ was even resurrected from the 25 O'Clock sessions.

“I think that Skylarking was sort of like us allowing ourselves to be more like the Dukes ‘seriously’,” says Andy. “But funnily enough, we probably took more care recording 25 O'Clock than we did recording Skylarking. It was certainly better engineered, and the playing had a bit more fire, because we didn't play Skylarking to drums. We played it to a click track and the drums were added later, so there was no band in the studio performing it, as such.”

“It's interesting that Skylarking was actuall recorded at the midpoint between 25 O'Clock and Psonic Psunspot, so it's all the same thing,” Dave points out. Andy concurs: “It's funny, now you mention it, 25 O'Clock, Skylarking and Psonic Psunspot... that's the Dukes records. Really is. I hadn't thought about that.”

Ah, Psonic Psunspot. As it happens, the second Dukes record — and only full-length album — ironically owes its existence to that '80s talisman, the compact disc. As Dave explains, “the aforementioned Simon Draper hauled us into his office and said ‘guys, check this out’ — and he had one of the first CD players in his office, he was so full of this. He said, ‘we can't put 25 O'Clock out on CD, it's too short. If you could do a Dukes Of Stratosphear album we could put 25 O'Clock on it and sell a CD of the Dukes’.”

So it was that XTC donned the purple paisley mantle of the Dukes once more and decamped to Sawmills Studios in Cornwall in '87 to record the album which began life entitled Psonic Psunspot Pstockade. “It was the perfect place to make a psychedelic record,” Dave recalls fondly. “You couldn't get to it by road, and any equipment that you wanted to use in the studio had to be loaded on to this tiny launch at high tide. I literally reversed hatchback as close as I dared to the water's edge and we manhandled the Mellotron out of the back and on to the launch. And to get it on to the quay on the other end, at the studio, you had two blokes with a rope.”

When XTC recorded Skylarking, Todd Rundgren's decision to tailor the album as a ‘concept’ — the span of a day — in which the songs could be construed as nebulously linked was regarded with a degree of scepticism within the band, although it did lend the finished product a satisfying roundness. The Dukes, of course, were no strangers to the concept of non-concept concepts. Psonic Psunspot features a track-linking ‘narrative’ by a little girl called Lily Fraser, daughter of the studio owner — now in her early 30s, unbelievably, and fronting her own band.

“She was brought in to do that thing where, ‘it's a concept album but of course it isn't’,” says Andy. “It's like Ogden's Nut Gone Flake, ‘what was all that bollocks about the fly and all that?’ It's not a concept, is it? Because the things are not related, really — let's be honest. Sgt Pepper sure, that's a concept album — not.

“So we had to have a concept album, not. We originally wanted Deryck Guyler to do the nonsensical stuff between the tracks — we couldn't have Stanley Unwin, too obvious, so we had to get somebody else with an equally daft memorable English voice. We contacted Deryck Guyler's agent but he wanted £10,000 to do it and the entire album budget was £11,000, so we ended up with all this Alice In Wonderland nonsense.”

Ogdens... fans familiar with Stanley Unwin's ‘Happiness Stan’ narrative on side two of the original album are vindicated with Dave's explanation that “on Psonic Psunspot the two sides are reversed.”

“That's right!” Andy cries. “Side one is side two. It was Virgin, they said ‘you've got to start off with ‘Vanishing Girl’, that's the commercial one’, so they flipped the sides. ‘You're My Drug’ is actually the opener, and ‘Collideascope’ would have been the closer.”

What a towering clutch of songs. Where 25 O'Clock came across in the main as more of an all-inclusive psychedelic collage or an aural splatter painting, Psonic Psunspot seems more specific in its remit as a succession of psych archetypes are reverentially hymned or playfully nudged in the ribs.

“Yes, you had to be careful because you could fall into the trap of just getting too Rutlesy with it,” says Andy. “But you still get crossovers, like ‘Collideascope’ is Lennon singing with the backing track of ‘Blackberry Way’, 'cos The Move were trying to do The Beatles as well. You do get these funny little smash-ups and things. ‘You're My Drug’ ended up a cross between The Byrds and ‘Monterey’ by The Animals, because The Animals wanted to sound like The Byrds, if you see what I mean.”

The soaring, jetstream rush of ‘You're My Drug’, in fact, first manifested itself as far back as the sessions for Go 2 in '78 and was shelved precisely because “it was too bloody Byrdsy.” ‘Little Lighthouse’, meanwhile — sounding to Andy like “those American bands that used to copy the Stones, like The Blues Magoos” — was rehearsed for Skylarking “because Todd suggested doing it,” says Andy. “He made up a loop of industrial sounds and Prairie Prince was going to drum along with that, but again it was, ‘Oh, this is too Dukesy, let's put it on the back burner for now’.”

Colin's crisply melodic contributions, similarly, were XTC holdovers. “All the things that Colin brought to the Dukes were actually songs that were primarily brought for XTC because he wasn't totally into the concept,” says Andy. “He took a bit of arm-twisting. So things like ‘Shiny Cage’ were actually rehearsed for Big Express, and deemed not quite good enough for that!”

“‘Vanishing Girl’ was meant for Big Express,” adds Dave, “but it sounded too much like The Hollies!”

“I don't think he wrote anything specifically,” continues Andy. “It was all a case of tweaking a few lyrics, and certainly looking at things stylistically, like ‘Shiny Cage’... ‘Well ok, let's approach ‘Shiny Cage’ like the entire Revolver album in one song’. With The Dukes, everything is vaguely something else. Even Colin's ‘The Affiliated’ was like, ‘well, let's try and at least make it connect to something in the mid-60s. Let's put on lots of ‘Concrete And Clay’ percussion...”’

“A real Austin Powers moment when that comes in.” smiles Dave.

Elsewhere, ‘Have You Seen Jackie’ neatly stitched together elements inspired by Mark Wirtz' Teenage Opera (“the kids, the ‘if you see him leave him alone’ bits”) and the Syd Barrett-era Floyd's ‘Arnold Layne’ — hence its original title of ‘Have You Seen Sydney’. Lily Fraser and her younger sister supplied the kids' chorus, for which they were given “a fiver each and some sweets”.

‘Brainiac's Daughter’ was the flipside to the Hylda Baker-assisted Lennonisms of ‘Collideascope’: Andy describes it as “an attempt to be McCartney psychedelia, specifically different, you know. Bubbles, ukulele, ocarina, ham-fisted piano, woolly bassline, drums in his kitchen and all that gear.”

‘You're A Good Man Albert Brown (Curse You Red Barrel)’ — which subtly salutes Andy's grandfather Albert Partridge and his grandmother Elsie Brown — came about because “every '60s band had the music hall song, whoever it was. I think The Kinks are to blame, because even The Stones did ‘Something Happened To Me Yesterday’. That's just pure Kinks music hall, you know, ‘how's your father, brown boots’...”

“English psychedelia is John Leckie in a striped blazer with a big gladiola in his hand, on the lawn, and someone's let off a purple smoke canister. Much more gentle, you're having a cup of tea and a plate of jelly in the garden with a rather nice-looking dolly bird in a crocheted mini-dress.”

“And that probably started because Ray Davies wanted to write songs that his dad could sing in the pub,” notes Dave, as Andy breaks into ‘Rene’ from Ogden's Nut Gone Flake by The Small Faces: “Actually, they were prime offenders!”

The creepy laughter which forms the segue from ‘Albert Brown’ to ‘Collideascope’ was inspired by ‘The Chrome-Plated Megaphone Of Destiny’ from the '68 Mothers Of Invention magnum opus We're Only In It For The Money: “I think that was Dave's idea,” says Andy. “I wonder how many people have spotted that one?”

The track on Psonic Psunspot which most clearly deviates from the British psych template is the exquisite Brian Wilson-inspired reverie ‘Pale And Precious’. “We were on a car trip up to London to see Virgin,” recalls Andy, “in '86, and Dave had Smiley Smile on the car stereo, and I'd not heard that album. I could just hear these little bits seeping through, you know, in the rumbling of the traffic and stuff, and I thought ‘what the hell is this’? I think Dave thought I was taking the piss. So I suddenly became a big Beach Boys fan in the mid-80s, so ‘Pale And Precious’ was a piece of new fandom as well as a thank-you. We caught Lily Fraser and her sister whispering secrets to each other between takes so we used a piece of that at the front of the track.”

So why did The Dukes adhere so closely to the British psychedelic model — the playful, childlike, ‘garden variety’ slant — as opposed to the US version? According to Andy, “American psychedelia is rather ugly — it's Vietnam, and student riots, and bad acid, and The Grateful Dead and Quicksilver Messenger Service... and Christ, if you can't play don't play for eight hours non-stop!

“But English psychedelia is John Leckie in a striped blazer with a big gladiola in his hand, on the lawn, and someone's let off a purple smoke canister. Much more gentle, you're having a cup of tea and a plate of jelly in the garden with a rather nice-looking dolly bird in a crocheted mini-dress.

“You know, people were trying to avoid the draft in the States, and the best thing Harold Wilson ever did was not get involved in that war. That, and to have teeth that he then lent to Shane McGowan! They are the worst. That thing where he's giving The Beatles those awards, look at his teeth! Jesus Christ, you're our Prime Minister and you've got Pogue teeth!”

“He had to have somewhere to stick his pipe,” suggests Dave.

“Yeah, it was like he had every other one knocked out! He could smoke three pipes in a row. But that was the best thing Harold did for England, never go into Vietnam. And the Americans were in Vietnam, and US psychedelia was sort of heroin, and ugly... it wasn't Alice In Wonderland.”

“At least the young were concerned about it,” considers Dave. “They knew what was going on, they knew it was wrong, and they had to say something about it. So they had the added distraction that we didn't have. We were still living in the slipstream of what The Beatles had created.”

“Because we are just talking about one year really, aren't we?” concludes Andy. “One year with six months either side, six months of '66 and six months of '68, and then it was, well... (Andy points at the nearby Shindig! article ‘Did The Band ruin British music?’) The Band spoiled it! Everything had to become brown and homely.”

So there were no plans to “update” The Dukes to '70 or thereabouts? No country rock, prog or proto-metal aspirations? “Well, we had talked about doing a prequel, which was a sort of Merseybeat-type Dukes,” remembers Andy. “In fact, I even wrote three numbers — in one afternoon. They were kind of like The Wimple Winch, just slightly pre-the Wimple Winch we know. Frantic Merseybeat on cheap booze. Trouble is, the Beat Boom Dukes would have just been The Rutles!

“There was some sort of chat about doing a glitter version, but I don't know if that was a goer. However, there was a bubblegum album planned for which there were a few things demoed — I actually started recording it in the shed, because I couldn't get Virgin interested in funding it. I went to see them and to play them some demos, and as Colin said it was like the scene in The Producers after they've watched ‘Springtime For Hitler’. They just sat there with their mouths open.”

Having been privileged to hear two authentically Kasenetz-Katz-esque tracks from the project — ‘Licky Licky Liquorice’ and ‘Cave Girl’ — Shindig! is pressing hard for closure.

Mention must also be made of the two tracks that were due to be pressed up as a double-sided freebie for Phil Smee's magazine Strange Things Are Happening. “Phil came down to interview us when Psonic Psunspot had just come out,” says Andy, “and he asked if we had any Dukes tracks we didn't use? I said ‘no, but I can do you some more if you like!’ It was going to be ‘It's Snowing Angels’ by Choc Cigar Chief Champion on one side and ‘Then She Appeared’ by The Golden on the other... then the magazine folded, so it never happened.” (‘Then She Appeared’ eventually turned up on the '92 XTC album Nonsuch.)

A coda is appended to the Dukes story in 2003 courtesy of Steve Somerset — who first entered the picture with his idea for a film treatment of 25 O'Clock. “Steve's wife, Hilary Freeman, has MS,” says Dave, “and he was anxious to do something to help the MS Society, so he thought ‘let's put together a compilation album, see if I can rope in as many people I know and ask them to contribute a track to this CD to sell for charity.’ He asked Andy if it would be possible to put The Dukes together to do one song for this little thing so Andy wrote ‘Open A Can (Of Human Beans)’, which was a reunion of sorts.”

Today, Dave Gregory describes himself as in a state of “semi-retirement”; not looking for session work as such, but happy to accept the right job when it comes along. Dismayingly, Colin Moulding is currently not in touch with his ex-bandmates (other than “exchanging bad-tempered emails,” in Andy's words, “but we'll see”). Andy Partridge, characteristically, remains tirelessly creative, intriguingly looking to go “beyond song” with Monstrance, featuring his old XTC colleague Barry Andrews, and collaborating on an open-ended project with fellow neo-psych icon Robyn Hitchcock which has resulted in two tracks to date.

One of them, ‘Turn Me On Dead Man’, is a tight, churning, Revolver-esque rocker which owes its title to the famous ‘Paul is dead’ rumour in Beatles lore: the repeated ‘number nine’ phrase in ‘Revolution No. 9’ is said to sound like ‘turn me on, dead man’ when play backwards. This, of course, is all grist to the mill for any self-respecting Dukes fan.

A most encouraging development is the possibility that Chips From The Chocolate Fireball, the CD which compiled both Dukes albums, may be reissued in expanded form with bonus demos, lyrics and copious liner notes. Andy says: “We've been negotiating with Virgin for about three years because they want to put out some old tracks for future compilations, and luckily we didn't have anything contracted to allow them to do that, so now we've hopefully got twice as good a deal as we had.”

To paraphrase myself at the start of this piece, I'm really glad in this instance that I got to meet my heroes. There was never any doubt in my mind that the people responsible for that unimpeachable, endlessly rewarding body of music would be anything other than gentlemen of considerable taste and refinement. Shindig! readers should however be cheered to learn that even after all these years of buffeting by the vagaries of fate, circumstance and litigation, Andy and Dave light up with enthusiasm when the topic of the Dukes and their antecedents is broached. They're fans, just like us.

Many thanks to Andrew Swainson for the photos.