|

|

|

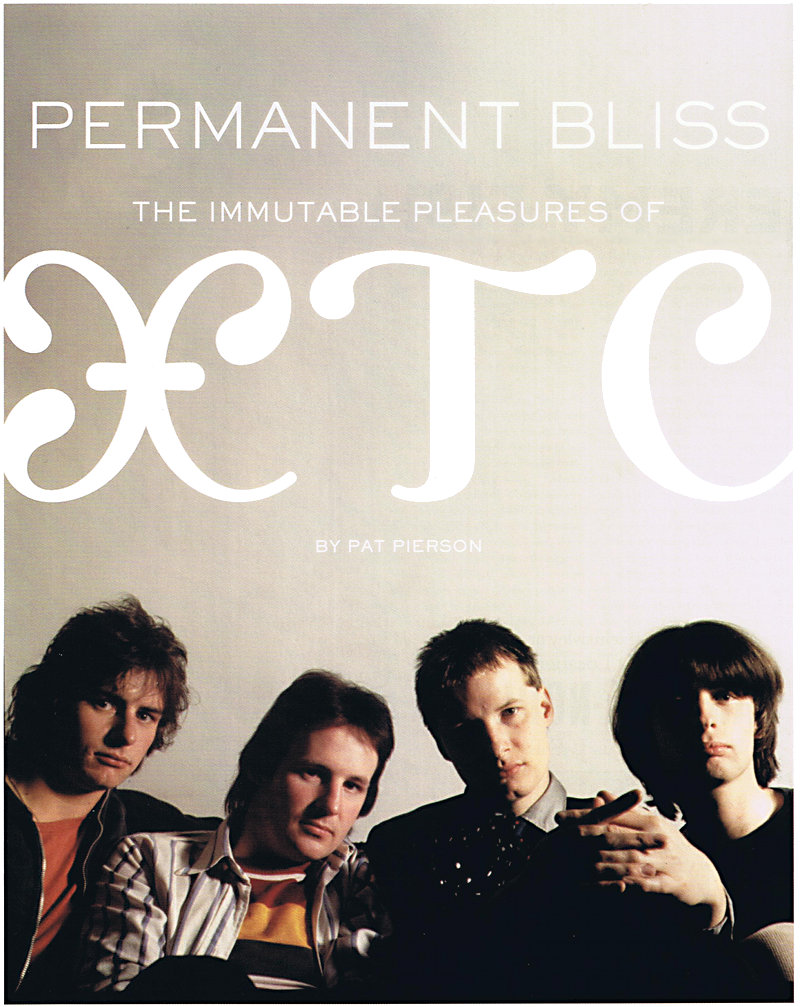

This is a pop-music story born when Britain was in the

throes of a musical revolution. As the 1970s waned, the upheaval that barely

scratched the American consciousness was altering the Brit-pop landscape just

as deeply as the Beatles had done 14 years before. But this time, instead of

mop tops and boyish charm, change came in the form of rebellious newcomers like

the Clash, the Sex Pistols, the Damned, the Buzzcocks, and a band called

XTC.

|

|

|

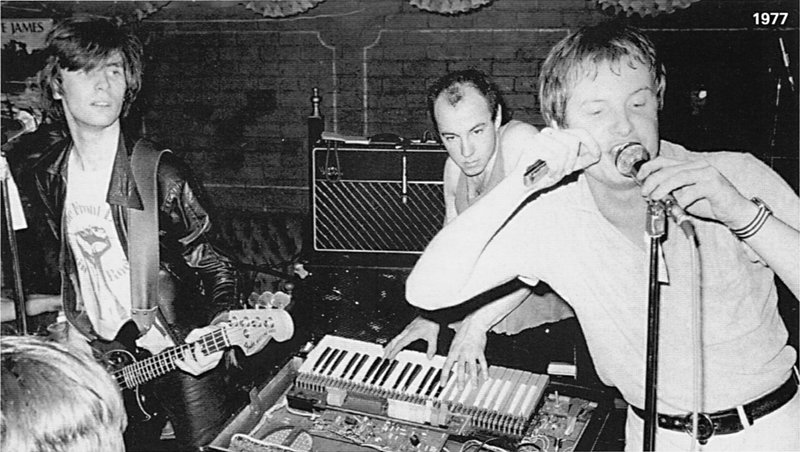

XTC was close enough to London to feel the proverbial kick-in-the-balls. Despite its out-of-step origins in a railway town named Swindon—a place with no pop or rock heritage to speak of—XTC would eventually become a caustic musical force; one that would span four decades and make guitarist Andy Partridge, keyboardist Barry Andrews, bassist Colin Moulding and drummer Terry Chambers heroes of the fringe. The band broke out in uncharacteristic punk fashion: slowly. Although XTC's early singles and immediate 1978 dent, White Music, were strong enough to inspire the likes of Gang of Four, it wasn't until the “hits” came in the form of “Making Plans For Nigel,” “Life Begins at the Hop” and “Generals and Majors,” that XTC became a veritable alternative band. And with the addition of Dave Gregory (who replaced Barry Andrews in 1979), the group was poised to take on the sorry 1980s. As is wont for any generation's cultural icons, most of the glorious transformers (i.e. the Jam, Joy Division and the Buzzcocks) quit before the age of 25. And most who played on sacrificed their identity for dance shoes and bad hair with the onslaught of MTV and cheesy movie soundtracks. Instead of Ian Curtis, we got Billy Idol. Life sucked. But while so many lost their way, XTC thrived by defying punk's naysayers and artfully avoiding the new decade's pitfalls. It charted waters to which no one was privy; while the band never released that breakthrough hit, XTC was always successful enough to keep its artistic vision. How else could we have gotten 1982's masterpiece, English Settlement, without some careful, ingenious balancing act? On an album that also netted the group's biggest U.K hit, “Senses Working Overtime,” Partridge expanded his biting worldview and the band melded punk with folk and world music. |

But the mold was cracking, and Partridge finally succumbed to personal demons that left him unable to perform on stage. The group had no choice but to stop touring, thus essentially becoming a studio band. However, Andy, Colin and Dave continued with their concept still intact, going forward with thought-inspired pop music as the '80s moved artistically backwards. The hits slowed, but the hardcore fan base never died. The quest for commercial success was always secondary, and perhaps due to the band's exile from the marketplace, it was a B-side tune that put them back in the spotlight. “Dear God,” a late addition to 1986's Todd Rundgren-produced Skylarking, became a fluke hit in Los Angeles via Rick Carroll's KROQ and eventually set off a resurgence in all things XTC. As teen pop boomed alongside hair metal and goopy synth schlock, XTC excelled artistically like no other band at the time. But progress would come to a halt in a sea change similar to how it began. In the early '90s, grunge quickly displaced the customary MTV drivel, and XTC found itself once again isolated from the major musical trend of the day. The group retired to home studios and embarked on a self-imposed exile until 1999, when it unleashed one of the finest farewells in pop history—Apple Venus Volume 1 and Wasp Star (Apple Venus Volume 2)—proving that their fastidious nature and refined sensibilities were the mark of classic craftsmen. In a nutshell: genius pop forever. |

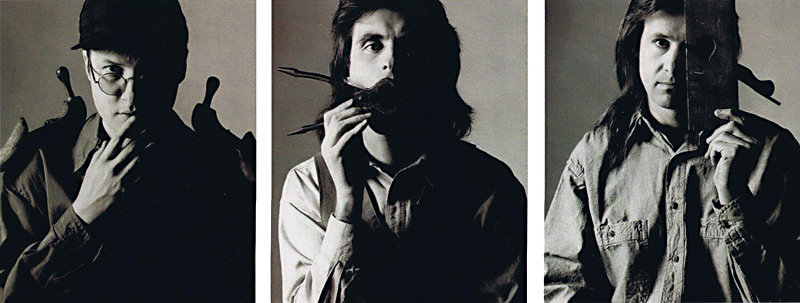

Andy Partridge, Colin Moulding, Dave Gregory

|

|

|

a conversation with What is the status of XTC? It doesn't exist in terms of people getting together and making music in the studio and saying, “Hey, I got some new songs.” It exists as a kind of brand name, I guess. Recently, I've been thinking of how I can reclaim it and possibly work with past members. But I don't know the legal whole or what Colin has over the name. I don't think he's interested in doing XTC anymore. And I think we have such a good reputation from the past that I'm scared of doing it in the future for fear of ruining that reputation. It's like you built yourself a mountain and you can't envision building anything higher than that—“I have to build something higher than what I just built? Surely that's impossible.” That's just my personal standards. Our lack of success commercially meant that I felt intimidated enough to really push each album to be better than the previous one. I would never be content to go on cruise control; that's just not me. And that lack of commercial acceptance helped. Like, “Well, you don't like that, and that was brilliant. We'll be doubly brilliant. Oh, they didn't like the doubly brilliant one? We're gonna be quadruply brilliant on the next one!” The band's longevity was amazing, especially for the '80s. Yeah, the big hair, shoulder pads and drum machines. Wow, we survived shoulder pads. With the exception of a few songs on The Big Express, we escaped the worst ravages of the '80s pretty okay. Even when you would try some '80s trend, it would still sound like XTC. It was organic. When we did do mechanical things, it was because we wanted something to sound specifically mechanical. And to some extent, I do like mechanical art. I quite like the Warhol-type repetition. I like the catalog mentality of lots of things the same. Sometimes you can get a certain effect with a mechanical style of playing or repetitive style of playing that borders on the trance or the pattern or the wallpaper effect. And if you look at a lot of our songs you'll find that repetition does play a big part, but hopefully it's a creative part. One time, producer Chris Hughes said to me, “You're the band who played their guitars like they were all sequenced.” And I know what he means. There was a lot of repetition. For bands like XTC in the late '70s, was the focus to exist in the art school side of the punk movement? The whole late '70s thing in England was a sort of vomiting. We had eaten such stodgy prog rock nonsense in the early '70s, I think people had to stick their fingers down their throats to make themselves sick. The whole thing was an attempt to get rid of this horrible stodginess. It was like, “Okay, let's make them shorter. The songs were about peace and love and crystal phoenixes.” No, they're not. They're gonna be about where I live. It's gonna be about this rotten state or this grubby tower block. You can see that it's that kind of cultural revolution. Let's go back to year one and turn everything on its head. In England, that was really needed. It's good to upset the furniture and smash stuff now and again. But I wouldn't want to live by that permanently. It was good for us to use at the time. And really, the whole punk thing enabled us to wander in and say, “Hey, this is what we do.” It was a great trajectory of sorts. Yeah, it was just like a big bomb that went “bang” and opened up the doors of resistance. Because we had tried with record companies before and nobody was biting. And then the punk bomb went off and doors came off their hinges. The record companies were like, “Whoa, let everything new in. Let's have a look. There might be some money in it.” In the early stages of the band there's a sense of agitation, but in the good sense; like John Lennon, where you use anger in a positive way. I think it's a mixture of youthful anger. For some reason, young men are angry. I don't know, too much testosterone, not getting enough sex. . . probably both. But it was a mixture of angry young men and fear. And the desperation, like, “This is gonna be our only album. We're only gonna get one shot at it. I'm gonna sing in such a memorable way.” I designed my singing quite artificially to make an impression. And it took me quite a few years to live that down. I think by Black Sea, I'm singing with my own voice. Then it gets more and more relaxed. The first two albums, I was definitely doing my theatrical-make-an-impression voice and that was coming through the angry young man-o-phone. Was there a point where you decided to say, “Hey, let's look at this a little bit deeper than the usual punk mind frame”? Well, with the punk mind frame, there really wasn't much of a mind frame. There was no mind to it. It was a big bomb. And I think that people who didn't go any further than that just stayed with its stupidity. And we're not stupid people. We all come from pretty poor backgrounds, but we're not stupid. We tried to educate ourselves the best we could and we don't like playing below our abilities. . . pretending to be less intelligent than we are has never been our style. There was a lot of flack for that in England. We were called “clever clever” and “smarty pants” and “brain surgeons from the West Country.” Even “Swindon Eggheads”! And really all of these handles were purely because we were trying to push music into a new area. And so we had to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous name calling because we refused to just play stupid. I never sensed that XTC got picked up by the “over-hyped” machine that's been in place to this day. You never became, as you once said of those who do get over-hyped, the “Flavor of the Minute.” Well, certainly in England we were considered to be amazingly un-cool. And that's fine, because I am amazingly un-cool. I'm quite glad and happy to be out hip and cool universe, 99.9 percent of the time, hip and cool have nothing to do with talent or ability or being good. It's about consuming. Does he have the right trousers or the correct shoes or the right haircut? We always had a trouser problem, you'll find. And with us, it was that lack of success that fired me up to make it better each time. You know, the world wasn't gonna ignore us, we were gonna get better each time around. And with XTC, the energy is always high, with no sense of aging—a very youthful kick. That's failure. Failure's fantastic. Failure is the best teacher. You can't buy failure. Is it ironic that [Virgin Records mogul] Richard Branson is in the “Generals & Majors” video? He's in that because he's a complete publicity hog. He heard that a BBC crew was making a documentary about us, so he arranged to slip the crew some money if they'd make a video for us on the cheap. Once they agreed, he decided he was gonna turn up and keep suggesting that he be in the video. That is the worst video ever made by man. But the indignity of having Richard Branson in it as well—because he wouldn't get out of it—added insult to injury. I was curious about all the Todd Rundgren stories with Skylarking, and why there was such friction. It wasn't like you hadn't worked with a producer before. What was different in this situation? I had never been told to shut up and be produced. It was a case of, “Well, they're the band and they make their music and that's why it sounds like that.” Virgin was desperate to have hits with us and I was told, “You've gotta have an American producer because we want you to sell in America and you gotta shut up and be produced. We don't want you making that weird-crash-bang-wallop-nobody's-gonna-buy-it music.” And of course, I'm not gonna take that lying down. Any interesting stories about “Dear God”? It got me a nice amount of hate mail. And some pretty wacky religious books people sent me. I have a few of them now—all to save my soul. It was very nice of them. |

an interview with What is your perception of the XTC legacy? Certainly Andy Partridge is a ground-breaking songwriter. We followed where the songs led, and by default broke new ground. After I joined the band in 1979 it comprised the standard two-guitars-bass-and-drums line-up—nothing ground-breaking in that. But the songs inspired a different approach to listening and playing from that which I'd grown up with. I simply couldn't continue grinding out old blues clichés and power chords, so I began to think more in terms of the songs as the masters and the instruments as the servants. We were among a handful of bands that emerged from the British punk scene who put music before attitude, although there was plenty of that in the early days. Andy had a sort of unwritten rule that everything we did had to be completely original; any hint of chop-ism, any rock clichés, any imitation of our fashionable peers meant the part—and in some cases the song—would be dumped! Not that there was ever any shortage of fresh ideas. As for our legacy, it's probably too early to say. We made around a dozen albums of unfashionable music that hopefully provided an edgy alternative to most of the industry pap that dominated the airwaves in the 1980s. What are your feelings about Andy Partridge and Colin Moulding's songs? How did each person shape XTC? Andy's songs tend to be incisive social commentaries, often acerbic, humorous observations of everyday life yet with a lyrical slant that isn't always comfortable to listen to. That may be why so few of his songs have been successfully covered by other artists. But he has this amazing gift for melody that can sugar the bitterest of pills. The fact that he is able to dream up new, quality songs virtually overnight when required validates his standing as an artist. And I've yet to meet anybody as prolific. Colin was in some ways an ideal foil for Andy, in others a thorn in his side. After his song “Making Plans For Nigel” became our first Top 20 hit, Colin began to fancy himself as the “writer of the singles,” and contributed perhaps two songs to every 10 of Andy's. In the interests of democracy, nearly all of Colin's songs would be recorded, occasionally at the expense of some of Andy's often superior offerings. This didn't always go down well, either with Andy or the band, but Colin did have some killer melodies and a sweeter sound to his voice that made a welcome diversion when listening to an album as a whole. However, Andy and Colin are both extremely competitive, which did lead to problems on occasion, particularly as Colin never repeated the chart success of “Nigel.” How was it in the early days with touring and videos and chart success? I suppose you could say that within a year of joining the group, most of my impossible rock dreams had come true! Apart from the obvious lack of money... but I honestly didn't expect it to last very long, so I relished every minute. My “audition” was a BBC radio broadcast in February 1979; we hadn't even played on a stage together. By June we'd released a single, done Top of the Pops, toured Britain, and were back in the studio making Drums & Wires. We shot two videos, toured Australia and Japan, returned to find the album in the charts after some rave reviews, with “Making Plans For Nigel” in the Top 20, and did a theatre tour of Britain which sold out! Then our producer, Steve Lillywhite, got to work with my hero Peter Gabriel on his third solo album, and called me to the studio to add some guitar to a couple of songs. 1980 was even more frantic. We did a grueling six-week tour in America in January, then flew home to rehearse and record Black Sea. Again, Andy and Colin quickly supplied another batch of fresh songs and we were back at work even before the jet lag had worn off. Then a summer package tour of Europe supporting the Police, who liked us enough to invite us to join them on their next American tour in the fall. We toured the States again in the spring of 1981: Todd Rundgren came to see us in Chicago. Virgin had licensed our catalogue to RSO, and [entrepreneur] Robert Stigwood himself turned up at a show at the Ritz in New York and told us we were the most exciting live band he'd seen since the Who! We returned home for a quick tour of Britain, but Andy was already feeling weakened by the treadmill existence of writing/recording/touring. Over the summer of 1981, he wrote most of what would become the English Settlement album. It produced our biggest hit, “Senses Working Overtime,” which made the British Top 10 and got the album off to a flying start in February, 1982. A world tour was set up to promote it, but at the end of the European leg Andy suffered a panic attack onstage in Paris. We came home, rested, then flew to the States to commence the U.S. dates, but only played one show, at the California Theatre in San Diego. Andy's health continued to deteriorate and we flew home, our performing days over forever. How do you think the band fits in with the mid and late '80s period, when you had success with songs like “Dear God” and “Mayor of Simpleton”? I don't think we ever “fit in” with any period, much less the dreadful '80s. Also, for much of that time, we were embroiled in litigation which meant we were effectively unable to work—even if Andy had wanted to. Because we were not seeing sales figures or royalty statements, we had no way of knowing how successful we were. We knew that “Dear God” had become a turntable hit and was a college-radio favorite, and that the video we made for it had been nominated for a number of MTV awards. That was encouraging though frustrating, because we couldn't get out there and take advantage of the promotion opportunity. I remember one day early in 1988, the phone rang and it was Andy telling me that a couple of Frank Zappa's band members were anxious to make contact with us. Andy and I drove up to Birmingham to see a show and met bassist Scott Thunes and “stunt” guitarist Mike Keneally backstage, and it became apparent from their conversation that our recent albums were hugely influential to many aspiring musicians and artists across the States. It was decided that since America was our biggest market, the next album should be recorded there with an American producer, which is how in the spring of 1988 we moved to Los Angeles for five months to work with Paul Fox on Oranges & Lemons. It was a hugely enjoyable experience, working mostly at a small production house, Summa, on Sunset Strip. Eventually the record was finished and released in a two-disc format in February 1989, initially flying off the shelves—much to our relief, as it had cost a small fortune to produce. In May of that year, the legal problems were resolved, leaving us with a phenomenal bill. We went back to the record company, caps in hand, and they agreed to advance another six-figure sum to pay off the lawyers in exchange for another four albums. How I love this business. Andy allowed himself to be persuaded to undertake a promotional tour of U.S. radio stations with the band to help push Oranges & Lemons, and to that end we grabbed our acoustic guitars and worked up some “campfire” song medleys from our catalogue. It soon proved to be very popular with both radio stations and other artists. It was hoped that this experience would whet Andy's appetite for performing again but it was not to be. We did return to New York the following month to perform live on the David Letterman Show, playing Colin's song “King for a Day,” and though considerable financial inducements were offered to re-form and tour again, Andy wouldn't even consider it. So we came home, and stayed home, where we remain to this day. I'm amazed—though thankful—that the records are still selling, and that there is still an audience out there who enjoys the music we made all those years ago. |

|

|

Failure's fantastic. |

A SELECTED XTC

DISCOGRAPHY Imitation may be the greatest form of flattery, but Andy Partridge isn't so keen on the fact that there's presently a new breed of bands sounding a lot like XTC circa 1979. The following five albums aren't necessarily the ones with the tunes that inform today's hipsters—for that, check out Black Sea and Drums and Wires—but we love 'em all the same. English Settlement (1982)

The Big Express (1984)

Skylarking (1986)

Nonsuch (1992)

Apple Venus Volume 1 (1999)

|

Go back to Chalkhills Articles.

[Thanks to Bill Wikstrom]

I was already making this album when my mind switched to where

I didn't want to tour anymore. But I think that this is the first time the

picture became multicolored and widescreen. Before that, it had been

television-sized format and rather black and white. It feels like a big

warehouse with lots of spaces between the crates.

I was already making this album when my mind switched to where

I didn't want to tour anymore. But I think that this is the first time the

picture became multicolored and widescreen. Before that, it had been

television-sized format and rather black and white. It feels like a big

warehouse with lots of spaces between the crates. My favorite from The Futurist Cookbook. It's kind of

industrial pop. We come from a railway town, and I was like, “Well,

let's wallow in that; in the imagery and the sounds. Let's make an album

that's riveted together and a bit rusty around the edges and is sort of like

broken Victorian massive machinery.”

My favorite from The Futurist Cookbook. It's kind of

industrial pop. We come from a railway town, and I was like, “Well,

let's wallow in that; in the imagery and the sounds. Let's make an album

that's riveted together and a bit rusty around the edges and is sort of like

broken Victorian massive machinery.” It came at a low point because we didn't have Terry Chambers,

and Virgin said that if the album didn't sell they were gonna drop us. Also, I

was told to shut up and let my music be produced, which I found difficult

because it is my music. It was very tricky for me, but we did a great job in

the end.

It came at a low point because we didn't have Terry Chambers,

and Virgin said that if the album didn't sell they were gonna drop us. Also, I

was told to shut up and let my music be produced, which I found difficult

because it is my music. It was very tricky for me, but we did a great job in

the end. A really grown-up record for us. The producer, Gus Dudgeon,

was an extremely old-school-'60s type and wore the tackiest Hawaiian shirts and

white satin trousers. Sometimes we laughed our socks off; others he was so

awful to me for no reason. But somewhere in all that, we managed to put

together a pretty damn good record.

A really grown-up record for us. The producer, Gus Dudgeon,

was an extremely old-school-'60s type and wore the tackiest Hawaiian shirts and

white satin trousers. Sometimes we laughed our socks off; others he was so

awful to me for no reason. But somewhere in all that, we managed to put

together a pretty damn good record. We did it all at once in Chris Difford of Squeeze's studio.

At first, Chris offered us free time but then asked for money. We didn't pay,

so he stole the master tapes and he's still got them to this day. We recorded

the whole double album once, basically. And then we started again, but I

didn't like the outcome. The third time we did it was the one we kept. I

guess one could look at the first two attempts as very expensive demos.

We did it all at once in Chris Difford of Squeeze's studio.

At first, Chris offered us free time but then asked for money. We didn't pay,

so he stole the master tapes and he's still got them to this day. We recorded

the whole double album once, basically. And then we started again, but I

didn't like the outcome. The third time we did it was the one we kept. I

guess one could look at the first two attempts as very expensive demos.